Malibu: “Like sex on a summer night”

|Cassidy George

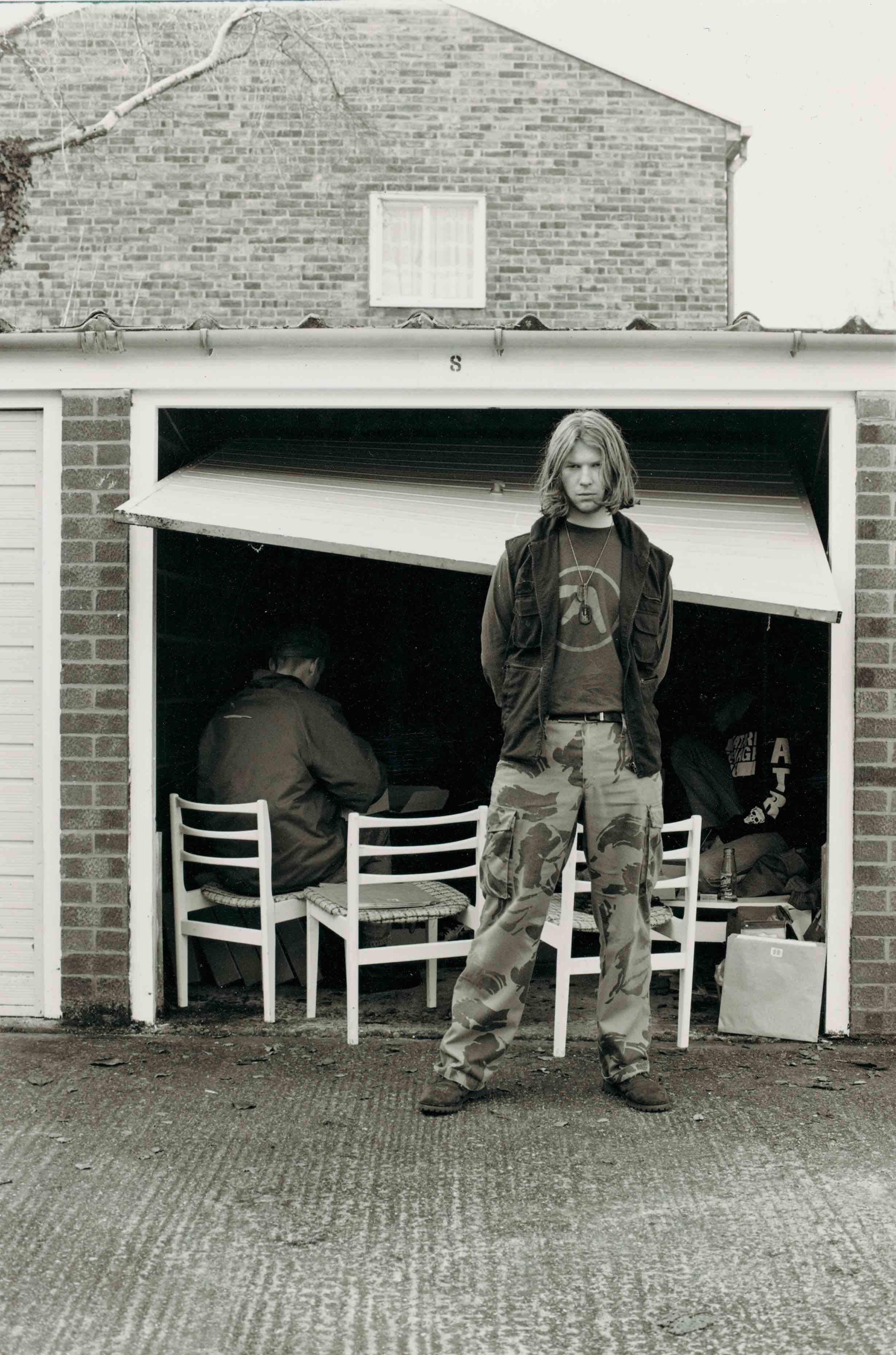

Barbara Braccini, also known as Malibu

If you ask a Californian to describe the ambient soundscapes of Malibu, they will likely mention the sizzle of sea foam on sand, the whipping of wind atop cliffside trails, or the symphony of silverware and celebrity gossip at Nobu. If you pose the same question to an erudite electronic music fan in Europe, they will likely wax poetic about Barbara Braccini, the French producer who goes by the moniker Malibu. Cosmic and divine, Braccini’s ambient soundscapes are gripping and ephemeral—her work references both the elemental and the socio-political, often layering synthesizers with spoken-word, samples, and field recordings.

Vanities album cover

When I spent an afternoon listening to Vanities (2025) in Malibu, the sounds of Point Dume felt like intentional additions to Braccini’s ambient epic. The slap of ice-cold waves against the asses of thong-clad influencers, the barking of seals and sea lions, and the muffled beeps of the alarm I triggered by parking a few meters too close to the driveway of a hilltop mansion only enhanced the layers and subtleties that already characterize the record. By allowing for even the most ungodly and neurotic to feel a temporary sense of connection with something bigger than themselves, Vanities serves a higher purpose than most contemporary music. It’s the kind of record I imagine healers in yurts in Malibu Canyon will play for wayward actors attempting to expel early childhood trauma.

On the album cover, Braccini inverts the Californian “land of milk and honey” trope with a foreboding image that evokes Paradise Lost. She stands in a glass house, overlooking hills and valleys, as an ominous storm brews on the horizon. Her record achieves a similar feat, inviting listeners to recognize the darkness and shadows that lurk beneath beautiful exteriors. Vanities also sounds like Paradise Lost—at various points in the album, listeners may feel as though they are eavesdropping on conversations between angels and demons in an alternate realm. In the weeks after its release, Braccini and I spoke about forced meditation, the hill she will die on, and the double meaning of her debut album title.

Cassidy George: I have the feeling that ambient music is enjoying a renaissance at the moment. I can’t tell if it’s because I am personally more aware of it or if it’s a broader phenomenon. Do you think its cultural value has remained pretty consistent, or have you also noticed a swell in interest and appreciation?

Barbara Braccini: It’s hard for me to tell because I don’t listen to a lot of ambient. I listen more to 1990s dance music or guitar bands and metal—well, only one metal band, The Angelic Process. So, I don’t actually know. But it does seem like a lot more people are making ambient. Like in 2016, when everyone was doing deconstructed club… maybe now everyone is doing ambient?

CG: I was speaking to a techno historian a few months ago and he told me that chill-out rooms with ambient were just as crucial to the development of early rave culture as anything played on the main floor.

BB: This is one of the hills I will die on—the idea that there needs to be a stronger culture of chill-out rooms at clubs and raves. I occasionally play DJ sets for more dance-music-focused festivals, and they always put me first because I play ambient or they somehow compartmentalize ambient away from the main dance floors. I think there was a different social context in the 90s. Back then, people in more rural areas of France would drive all the way to Belgium just to go to one club or party, or for the chance to rehear a track they heard the previous week. In this case, the chill-out room had more importance just based on the fact that people had driven all day.

People who do it well now are the crew behind Trance Party. They understand and know the exact vibe. They’ve been trying to do chill-out rooms, but it’s more difficult and expensive, because you need more space.

CG: Listening to your music feels like a short cut to an elevated state of consciousness or being in the presence of something holy. I’ve always wondered if you are religious or if you had a religious upbringing.

BB: I was baptized Catholic and did my first communion, but I’ve always rejected authority. I hate being told what to do and what is right and wrong. When I started doing Bible studies at school, I would always be the class clown and ask annoying—but valid—questions. I was defiant against the entire model and rejected the idea that things can only be one way. I hate when people impose their beliefs on you, and this is the case for any authority figure in my life. I think religion should be a personal path to discovering whatever you find peace and purpose in.

I would like to be more spiritual, but I don’t know how, and this maybe translates into how I make music. I don’t meditate, but when I’m on stage I stand very still and press buttons for hours. It can be entrancing, looking at blinking lights and numbers, and switching things on and off. I’m sort of forced to meditate during that time. Whenever something goes wrong or takes me out of that state, I’m extremely frustrated.

CG: Your music is based on stories and events in your life, but how do you tap into the frame of mind that allows you to compose? Would you call it a flow state?

BB: Yes and no. Ideally, the idea for a song comes because of a strong emotion or a reaction to something—like being broken up with, even though that’s a bad example. You don’t have these kinds of feelings every day. Most days are spent in apathy. Lately, I’ve been asking myself how I can make music if I’m not being broken up with every day!

In the last few years, I was working in a studio with synthesizers, mostly because I didn’t want to be in front of a computer. It’s kind of like how someone with writer’s block doesn’t want to look at a blank page. I would play synthesizers for hours and record whatever came out. Most of it wasn’t good, but then I would hear maybe five seconds that were, and that would become the basis for a new track. It’s not really about being in a flow state, it’s more just a question of time. I lose all sense of time in the studio, just as I do when I’m playing live. I’m suspended in the moment.

CG: I think the average music fan would consider ambient as the ultimate blank page. Can you explain what’s going on inside of some of your tracks on Vanities, or how you made them?

BB: “Lactonic Crush” is a good example of the five-second process I was speaking about. The first part was made with five seconds from a two-hour synth recording that I EQed. The second part is the same five seconds pitched down and stretched, which results in a completely different sound. On this part, I recorded my voice and added some spoken word and singing on top. The third part is a tiny, five-second part of the same sound that I didn’t even loop a second time, because twice felt greedy. Overall, the process was quite simple, but there was a feeling to the melody that I cannot describe. It felt very sultry and nocturnal, like sex on a summer night.

The last track on the album is called “Watching People Die.” It consists of recordings from the movie White Oleander (2002), sounds of car keys jangling, someone getting into a car, and a piano melody from a song by Future Sound of London that I love called “Lizard Crawl.” I remade the melody and sang over it for a radio show, but I loved it so much that I wanted it on the record as well. It’s still quite simple in the end. If you look at my projects, there is not much to explain—it’s all about a feeling, one that I am unable to describe with words.

CG: Can you shed some light on the double entendre of the name Vanities for this record? I read that you originally planned to go with the French word vanités, which has a different connotation. How do you understand both in relation to this project?

BB: It’s inspired by this painting genre called Les Vanités.

CG: Seventeenth-century still-life paintings, right?

BB: Yes. I was drawn to the idea of compositions filled with arrangements of personal objects and what they represent—like a skull symbolizing death, for example. Everything is really about life and death. It sounds broad and basic, but there’s not much more than that, is there?

Many of the records on the album are quite short, which I was feeling insecure about for a long time. I went to a friend for reassurance and they said that the songs on the album are kind of like the little objects you might find washed up on the beach. These small things that we collect and assign meaning to, and that come to represent something else. Nothing really has meaning unless we give it meaning. Otherwise, it can start to feel like there’s no point—and if you accept that everything is meaningless, then it’s like: “Okay, why not just kill yourself?” [Laughs] I’m exaggerating, but that’s how it feels sometimes. At the end of the day, life is for living, and I want to enjoy the little things.

I became very interested in the idea of a collection of sounds as objects, and the apathy of living in today’s age. Everything feels quite harsh nowadays. It’s hard to be excited about anything if you are looking outside and aware of how corrupt everything is. That’s why I called the record Vanities. It’s not about vanity. Of course, that’s part of it, but the idea is much bigger. I didn’t want it to be about me looking at myself—it’s about all of us.

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George

- Images: Igor Pjörrt

Related Content

Drain Gang

GOLDRAUM 1 by Hendrik Schneider and Tom Schneider

ABC of AFX

No More Ghosts, Please: On Taste and NTS Radio as an Antidote to AI Slop

CALABASAS

Wolves and Thistles | Varg²™

Gated Nightmares: Herrensauna’s Cem Dukkha

Ways of Raving: Geoffrey Mak on Empathy and Psychosis

JAMES BLAKE Seeks A Higher Vibration