Jon Rafman: When Dreams Become Reality They Turn Into Nightmares

|Claire Koron Elat

Cloudy Heart's profile picture on various streaming platforms

Last week, Jon Rafman’s AI avatar Cloudy Heart released $REAL, an album that obscures the distinction between human emotion and machine logic. According to Rafman’s team, the work “unfolds like a transmission from the heart of the algorithm: desire, grief, propaganda, and poetry compressed into sound.”

To mark the new release, we are republishing Claire Koron Elat’s feature on Rafman from 032c Issue #46, which explores his ongoing fascination with virtual subjectivity, synthetic intimacy, and the psychic fallout of life online.

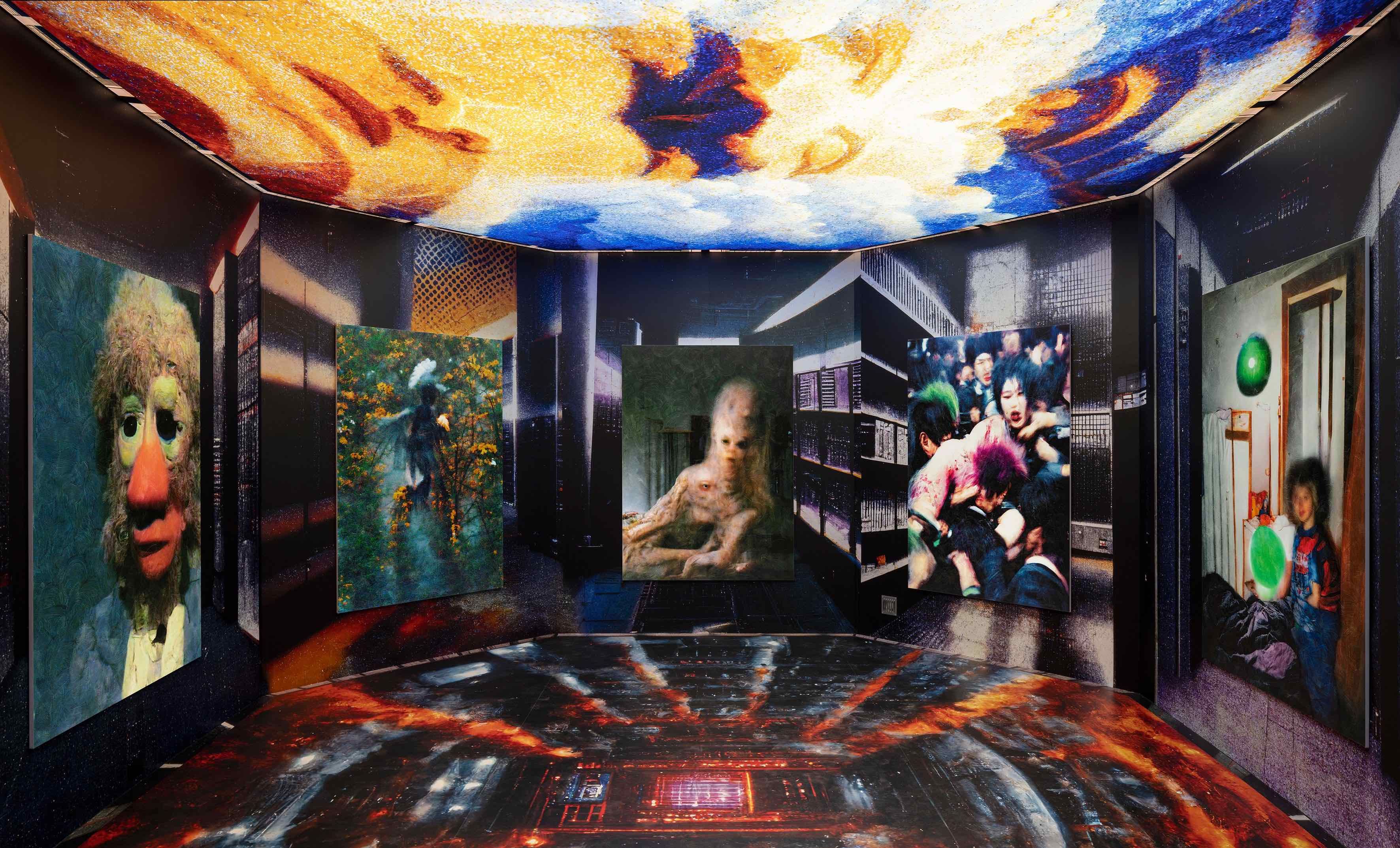

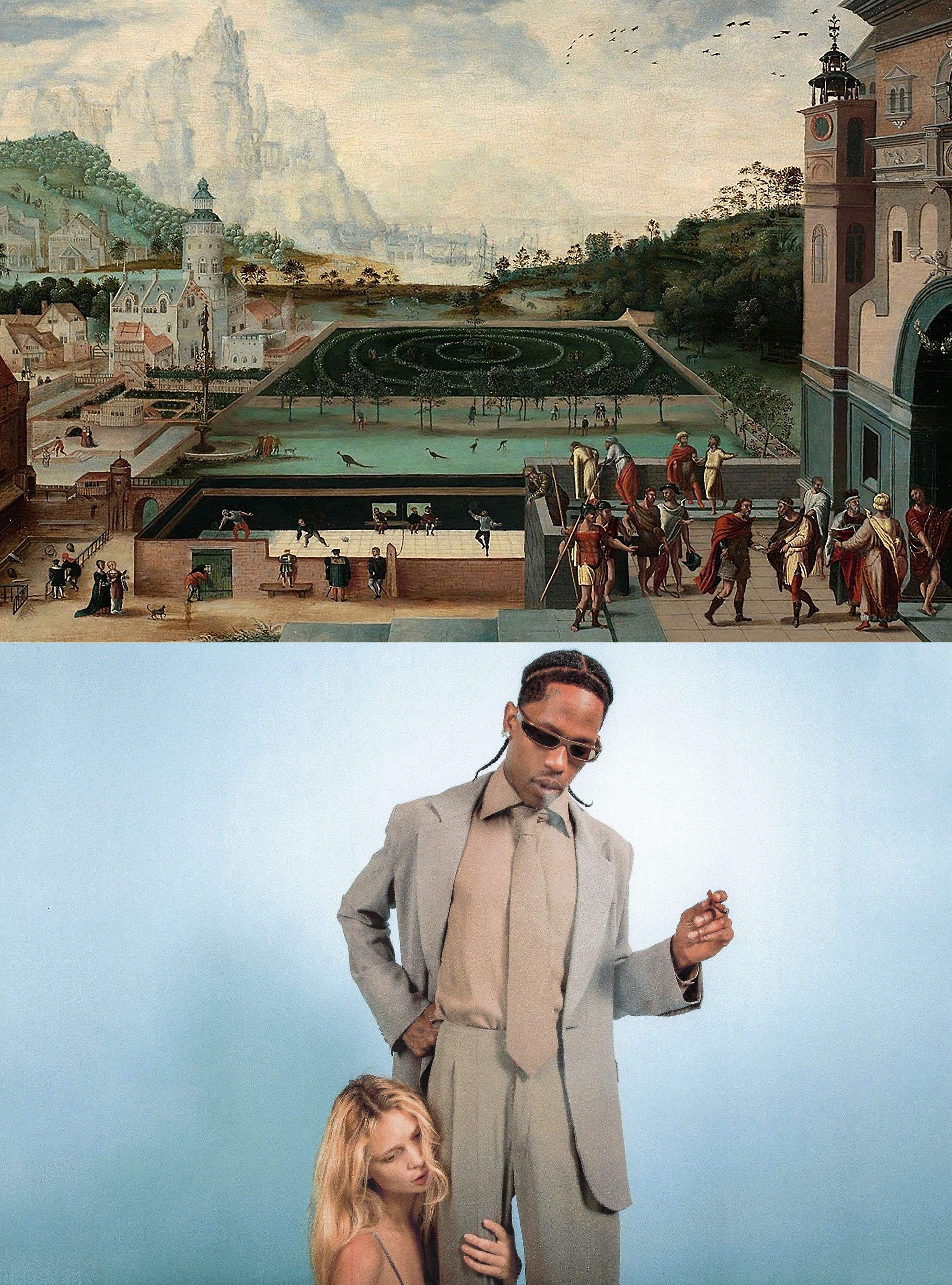

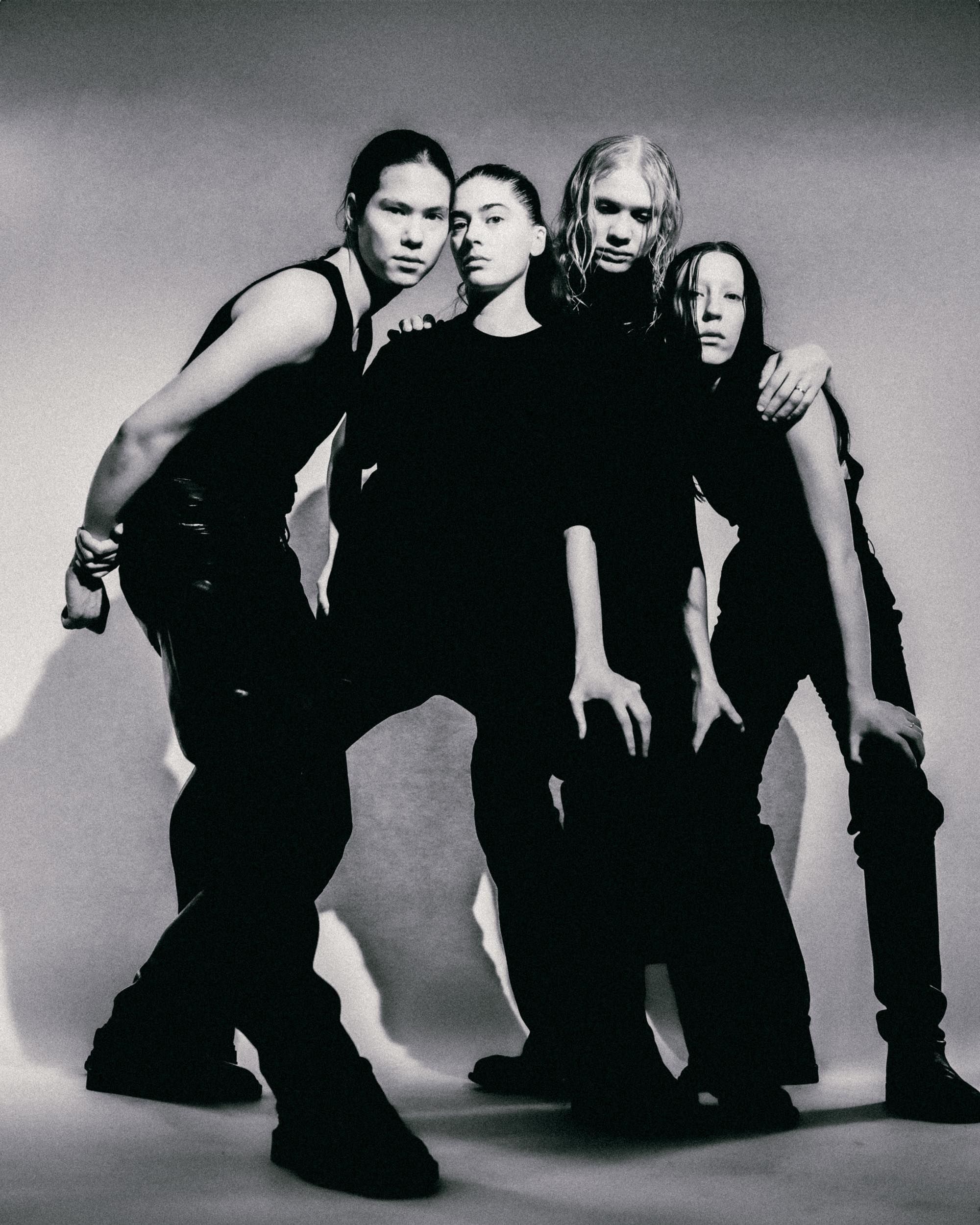

For this interview JON RAFMAN created all images exclusively for 032c.

In Andrei Tarkovsky's 1979 science fiction movie Stalker, the protagonist, known as “the Stalker,” guides a writer and a professor through a seemingly endless, unpredictable, and dystopian wasteland. The aim is to arrive in the Zone, an uncanny, restricted site that is home to a room that acts as a mirror to your soul, fulfilling your dreams. But instead of dreams becoming pleasant reality, Tarkovsky suggests that one's subconscious desires might better be left unknown, the room in the Zone unentered. As one of the greatest directors in cinema history, Tarkovsky explores the depths of human existence - navigating through dystopian environments and hidden desires on a quest for the genuine, unapologetic self.

These are themes that artist JON RAFMAN likewise explores. In his video work Kool-Aid Man in Second Life (2008-11), a protagonist distantly reminiscent of Tarkovsky's Stalker wanders through an infinite landscape. In this eccentric and at times dystopian environment that makes reference to the user-generated virtual world Second Life, distinct symbols, free from historical attribution, float about, and Rafman's avatar, called Kool-Aid Man, is a reminder that when dreams become reality, they might quickly turn into nightmares.

Rafman's work deals with such fever dreams that exist in an ambiguous realm between the real and the virtual, coalescing in marginal, fetishistic, and occult forms. The warped faces and melting bodies present in his video works and Al paintings question our experience of modernity. Having always referenced wider pop culture in his work, Raman has increasingly started collaborating with artists including Ye, Travis Scott, Shayne Oliver, and Lil Yachty. For Oliver, for example, Rarman Generated Al imagery based on the designer's moodboards and ideas that then informed the pattern-making. Rafman uses these kinds of collaborations to expand into much larger conversations than those that exist within the art world.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: I want to start with something you said around four years ago in a different interview: you've never wanted to be an art-world artist, you wanted to be connected to culture at large. Is this something you still believe in?

JON RAFMAN: From my experience - perhaps because I'm getting older - it feels like the art world is less relevant than when I first started. The market, gallery, and museum system seems disconnected from where culture is headed, almost ghettoized. I've found myself naturally creating work across different cultural fields, and I see more artists doing the same. That's what makes this moment exciting; I feel more energized than ever to create art, especially with all the new tools we have.

CKE: How has the art world changed since you first started?

JR: I read that EDGLRD - Harmony Korine - called [the YouTuber and online streamer] IShowSpeed “the Tarkovsky of our time.” It sounds tongue-in-cheek, but there's truth to it. Culture has moved so far from museums and galleries, and now it's being shaped by these online creators. Figures like IShowSpeed are, in a way, today's cultural vanguard. There's something Warholian in what they're doing, too - transforming the everyday into something compelling and somehow more engaging for kids than heavily produced media.

CKE: Who would you say is the Tarkovsky of our times?

JR: You have to take these grand statements with a grain of salt, but there's truth to the idea that online creators are changing how we engage with media. There used to be more of a monoculture, where everyone was tuned in to the same media. Now, society and modern media consumption are so fragmented that the whole cultural landscape feels impossible to capture. I'd bet most people over 30 don't even know who IShowSpeed is. Culture today thrives on niches - an influencer can have 20 million followers yet still be virtually unknown outside their specific bubble.

CKE: If culture is fragmented to that extent, how can you be an artist who perceives culture as a whole? Do you think you have to consider culture in this holistic sense to be a good artist?

JR: On some level, we're all connected through the internet, but it's harder to make broad statements about culture now. I try to engage with spaces that feel most relevant to young people, like gaming or streaming. Even in this fragmented world, I want to use universal languages. We don't have the same shared narratives we once did - like the Bible. Instead, we have new reference points that help people connect. That's why I started making internet art; it feels like the closest thing we have to Greek myths today. Memes are almost like modern mythology, a shared language people use to communicate across boundaries.

CKE: There are still “hardcore” art-world people who negate the tremendous influence of contemporary pop culture because it doesn't seem intellectual or “chic” enough. Maybe it's more applicable to older generations, but there are people who don't know Ye or Travis Scott and think they're not valuable for cultural discourse.

JR: Art should constantly question and critique itself. For example, the rise of Al image-making is something artists can't ignore. Suddenly, anyone can create images in any style, instantly and cheaply. This shift puts real pressure on art to redefine itself. If you want to stay relevant, you have to confront this new reality. At the same time, there's still a place for art rooted in tradition - just like there's a rich niche subculture for people who collect Super Soakers, McDonald's Happy Meal toys, Beanie Babies, Tamagotchis, old-school Pogs, original Furby dolls, and so on. It's important to remember where we came from. When I started making internet art, I wanted to bring elements of history - Western culture, literature, philosophy, and art history - into this online world that's often ironic, absurd, and surreal. One of our biggest risks today is forgetting. We can't let the past become something lifeless that young people can't connect with. To keep it relevant, we must find ways to make it feel fresh and new again.

CKE: So that means we only work with ideas that have existed before?

JR: Nothing exists in isolation. I might be labeled as pessimistic or nihilistic, but I see it differently. Artists who confront harsh realities head-on - like Beckett - are often less cynical than those who avoid them. Facing the brutal truths and horrors of life is a more genuine approach than evasion. Engaging with this reality is essential if we want to create something meaningful today.

CKE: So, would you say that optimists are the true cynics?

JR: Just because someone's work seems pessimistic doesn't mean the artist is a pessimist. It's essential to separate the art from the artist. Sometimes, works that claim to serve a social cause or promote progress feel the most cynical to me - maybe because they're created with a certain self-righteousness or assumed moral high ground. History shows us that even the worst actions can be carried out with so-called good intentions.

CKE: Do you think this complexity is amplified by social media and the way it shapes our identities?

JR: Absolutely. Social media constantly shapes both our perception of the world and our self-image. We create versions of ourselves online, but these are heavily influenced by how others react to them, which in turn affects how we see ourselves. This continuous feedback loop can make it easy to lose sight of what we genuinely think or believe. That's why it's essential to question the role social media plays in our lives if we want to understand ourselves in such a rapidly changing world. The paradox is that while everything feels like it's moving forward, there's also a deep sense of stagnation.

CKE: You mentioned the phenomenon of finding a niche. There is a trend where creators and brands specifically niche-down or only cater to a specific group with more highly specialized content instead of addressing a mass audience. Do you think this is rooted in an increased division of society?

JR: The internet definitely played a role in this. It both brings us together and drives us apart. In the past, if you lived in a small town with one dominant culture, you'd be pretty isolated in any niche interests. Now, anyone can connect with people who are into the same specific things - whether it's collecting vintage Pez dispensers, playing obscure Japanese visual novels from the 90s, or studying medieval alchemy recipes for immortality. On one hand, this connectivity allows niche cultures to thrive in ways they couldn't before. On the other, it contributes to a more fragmented society, where people can end up existing in highly specialized bubbles rather than sharing a common cultural experience.

CKE: For your series “Egregores,” you used this concept from Western esotericism. An egregore is a non-physical entity or thought form that arises from the collective thoughts and emotions of a distinct group of individuals. Recently, you showed the short video clips at 032c's store in Seoul. These were sourced from the internet and looked at the internet from a lens of mysticism, right?

JR: With “Egregores,” I was trying to bring to life these strange, almost mystical images I found online. I'm fascinated by internet mysticism, which is why I called them egregores - it's like they have an energy of their own. There's this idea of “meme magic,” where certain images carry a kind of lore that fuels their spread. I wanted to create these visual poems that work as moving paintings with uncanny animated elements, designed for Instagram. Over time, they took on a life of their own and formed collections that, when played together, feel like triptychs on a wall, full of juxtapositions.

Much of the process is instinctive; I think it's essential for artists not to overthink. Reflection comes later - in the moment, it's more about channeling something raw and visceral. The other works in the Seoul gallery also draw from this surreal, absurd imagery I've absorbed over the years, blending landscapes and characters shaped by online “shitpost” culture.

CKE: The second series you showed was originally constructed for the virtual realm and video games. It investigates world building and features characters such as a young, fully armed girl who has an owl/dog hybrid standing next to her; an old, witch-like woman wearing a yellow plastic coat and carrying a bunch of shopping bags; and a human/reptile hybrid in a red and-blue spiky spacesuit. Where do these figures come from?

JR: These characters emerge from a mix of my input and the Al image generation software. There's always an element of surprise - that's part of the beauty, like tossing paint and seeing where it lands. But over time, I've learned to work with the algorithms, almost like learning an instrument, finding through trial and error how to bring out specific qualities.

CKE: The notion of building your identity as a form of creating your own avatar also relates to another 032c show your work was shown in, “Productive Narcissism,” the inaugural exhibition of 032c Gallery in Berlin this fall. We were inspired by Boris Groys' essay “Self-Design, or Productive Narcissism” (2016) in which he talks about how the notion of narcissism has changed. In the past, the narcissist identified their own perspective with an “objective” social perspective and assumed that others would be fascinated by their image of the world. But the contemporary narcissist can't be certain of their own taste or rely on the looks they were born with; they need to constantly adapt to the changing taste of society.

JR: Exactly. Narcissism today is heavily shaped by how others perceive us, especially with social media amplifying that feedback. In the past, while narcissism still involved seeking admiration, it was more self-contained - less constantly mediated by the gaze of others. Now, identity is filtered through how others consume us online, making external validation almost constant.

CKE: You're also quite interested in other online cultures, such as incel culture. One phenomenon in that culture, called looksmaxxing, is about changing and maximizing your natural appearance. The idea is that you are not content with how you look without alterations. In some ways, it reminds me of what Groys wrote about. He is saying that you can't rely on the looks you're born with, you need to adapt to become society's standard.

JR: Looksmaxxing is just one example of how the internet has influenced how we see ourselves. Plastic surgery, Photoshop, and filters have become part of everyday life, and there's now this idea that many aspects of our appearance - and even our identity - can be shaped and reimagined through technology, both online and offline. I can imagine a future where augmented reality glasses let us change how we see others, too. If you wanted to see your partner differently, for example, you could put on AR glasses, and suddenly they look like someone from your fantasies or an entirely different persona. So it won't just be about altering ourselves; it'll also be about reshaping how we perceive other people.

CKE: Do you think that's cheating?

JR: I don't really believe in strict notions of authenticity, but I've noticed that many people have strong reactions to Al, even anger, because they fetishize the handmade as somehow more “authentic.“ Clinging too tightly to that idea ignores the reality of our technological age. Now that an image can be created in seconds instead of years, artists have the opportunity to explore fundamental questions about the nature of art itself and its purpose in contemporary society. This shift challenges us to rethink not only what art can be, but also how it navigates our lives in a landscape that is both interconnected and deeply divided - especially as the lines between the virtual and physical realms increasingly blur.

CKE: What you're saying about the virtual and physical collapsing - and also the virtual being heavily present in mass culture - made me think of how, in the past, video games were this super geeky thing outsiders played in their dark apartments, and now you have major fashion houses collaborating with video game brands. When do you think video games suddenly became cool?

The whole concept of “cool” keeps shifting. Video games are a perfect example - they've gone from being this niche, outsider thing to dominating both commerce and culture. But it's part of a bigger shift - it's the “revenge of the nerds“ playing out across society, from Marvel and Star Wars becoming the center of mainstream entertainment to anime influencing everything from fashion to music. What's fascinating is how these formerly fringe internet cultures have reshaped everything - from how we dress to how we communicate to what we value. These spaces that used to be considered geeky or antisocial are now where most cultural innovation happens. It's not just about tech becoming mainstream; it's about how these outsider perspectives have become the lens through which culture now sees itself.

CKE: Previously, you mentioned that art has become more “ghettoized,” but you and others have brought art into other spheres. And as such, art has started to seep into other cultural production at large. But where do you draw the line? Is a music video always art?

JR: This raises important points about how we define art and whether there should be limits to that definition. If we say that everything can be art, doesn't that risk losing the meaning behind it? Personally, I believe art shouldn't just have a function. For instance, advertisements often don't count as art if their main purpose is to sell something. Even propaganda can have artistic elements, but that intention can lessen its value as art. I think there's something to the modernist idea that art is meant to be purposeless. That lack of a specific purpose allows art to have freedom and autonomy, which keeps it from being just a tool. When art becomes too functional, it can lose its essence. But it's also important to remember that the definition of art is always changing.

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat

Related Content

No More Ghosts, Please: On Taste and NTS Radio as an Antidote to AI Slop

EDGLRD: Harmony Korine Sets Technology Aflame

Finding Romance in the Grotesque: JON RAFMAN

NON-REFERENTIAL: Travis Scott in dialogue with Valerio Olgiati

“DEVILS ON HORSEBACK” Curated by Claire Koron Elat and Shelly Reich

“I AM THE LEADER”: YE (KANYE WEST) in Conversation with TINO SEHGAL

Fake Press for a Fake Band: Reece Cox

YEAR OF THE PIG: JON RAFMAN and the World’s Hungriest Fetish

Brenda’s Business with SHAYNE OLIVER

Productive Narcissism