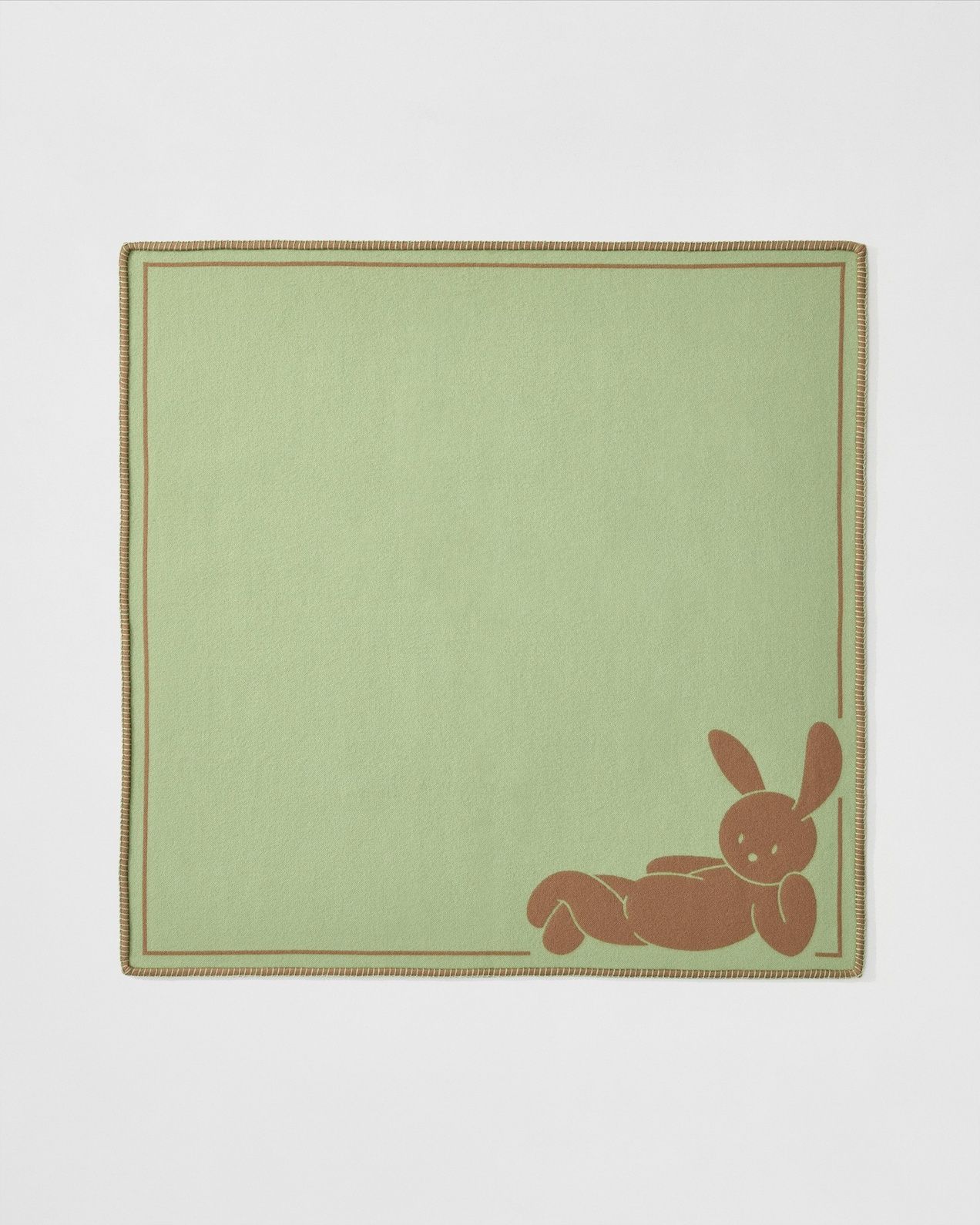

Raf Simons’ Teddy Bear: Kvadrat/Raf Simons AW 2025-26

|Shane Anderson

Too much in this world has gone grey. Cars, phones, computers—you name it. But designer Raf Simons still believes in the power of color. His decade-long collaboration with Kvadrat, for instance, began as a protest against this flattening of the visual world and as a question: how do we actually live with things? The latest chapter of Kvadrat/Raf Simons adds new textiles—some of them, joyfully bright—and, for the first time, objects for children: teddy bears and hooded towels included. For Simons, design should serve real life: homes with dogs and kids and mess and not just the pristine rooms of magazine spreads. In this conversation, he talks to Shane Anderson about his own childhood, his philosophy of color, and what he’s learned from people-watching with Miuccia Prada.

Photo: Willy Vanderperre

Shane Anderson: What did you wear as a kid?

Raf Simons: One of my early memories was from my first communion—you know, I was raised Catholic—and I had a white turtleneck with jeans, a jeans jacket, and a necklace. It was very 70s, obviously. I probably didn’t choose it but I loved it.

SA: I don’t think kids really get to choose what to wear for such occasions.

RS: Exactly. And when I did my Holy Communion at 12, my mom chose my outfit too. I hated that look so much that I destroyed all the photographs. My mom was always really mad about that.

SA: What were you wearing?

RS: I don’t know what it was like anymore but I think it was a bit snobbish. White shoes and a knitwear thing. I really hated it.

SA: And when did you start dressing yourself?

RS: I think soon after that. I was like “hard stop.” At the age of 13 or 14, I definitely decided what I was going to wear. It was really myself. And then came New Wave—you see, I was born in 1968, so I was too late for punk. I was in a very classical Catholic college, where everyone was expected to go on to law or medicine, but a few other people dressed like me. It was not welcome but we did it anyway.

When I had to decide what I wanted to do, I visited one school, which just happened to be the school for industrial design. I remember it as if it were yesterday. I took the bus and arrived at the university and saw all these people dressed in really extreme ways, sitting outside smoking cigarettes. I took the bus straight back and told my parents that’s where I want to go to university. At that point, I couldn’t have cared less if they taught fashion, industrial design, or interior design. In the end, I did like that education very much. That was also during the rise of the Antwerp Six and Margiela. I remember saving money for a whole year to buy a pair of shoes or a sweater from one of them.

SA: But you didn’t study in Antwerp, right?

RS: There are two schools with industrial design faculties in the Flemish-speaking part of the country. One is in Antwerp and the other’s in Genk. I decided to go to Genk because it’s focus is more on the language of form and social responsibility—it’s more philosophical and art-oriented. The one in Antwerp is very technical. I wasn’t a very technical person and I found it attractive that some of the teachers in Genk were also artists.

SA: If everyone was expected to become a doctor or lawyer at your school, was industrial design a sort of middle way of doing something respectable but then also artistic?

RS: No. Studying industrial design was not a break with what was expected from me because my parents never imposed anything on me. My dad was an army night watchman and my mom was a cleaning lady. They never said what I should do. I remember coming home one night and complaining about school at the age of 15 or 16 because I hated certain subjects and my mom said, “Would you like to clean for the rest of your life?” She just posed that question, which I didn’t even answer. That was it. From then on, I made sure that I did well. Not the best in class—but not the worst either.

I actually liked going to school though since my friends were all there and I loved subjects like history. And then, when I was at university, there was philosophy and sociology, which I loved. This is going to sound pretentious but I was always one of the best in class for anything to do with design or proposing idea for probably five years straight. I was a disaster in all the theoretical courses though, because I no longer cared. I wouldn’t go to the lessons and would just ask my classmates to look at their notes two weeks before the exams. I’d sit in the church in June and study there because it was cool. I was just making sure that I wouldn’t fail.

SA: You said you enjoyed the philosophical and sociological aspects of the coursework. Did those find their way into your designs?

RS: I think so. And I also think that it informed the way I like to live my life and how I surround myself with objects.

SA: How?

RS: For example, we live with a very big dog and we’re not the kind of people who say that the dog isn’t allowed on the sofa or on the bed. Basically, the dog has more freedom here than anyone else. And we love that. We want the dog on the sofa or in bed. The point is that furniture needs to be at the service of people. But the way the industry has been evolving, there’s a real split. You have these gigantic companies working with designers and architects to design pieces, and then you have these places that are almost galleries, creating furniture that has a more artistic look. But that’s a world I don’t put in my house. I’ve never bought furniture pieces that are more like objects.

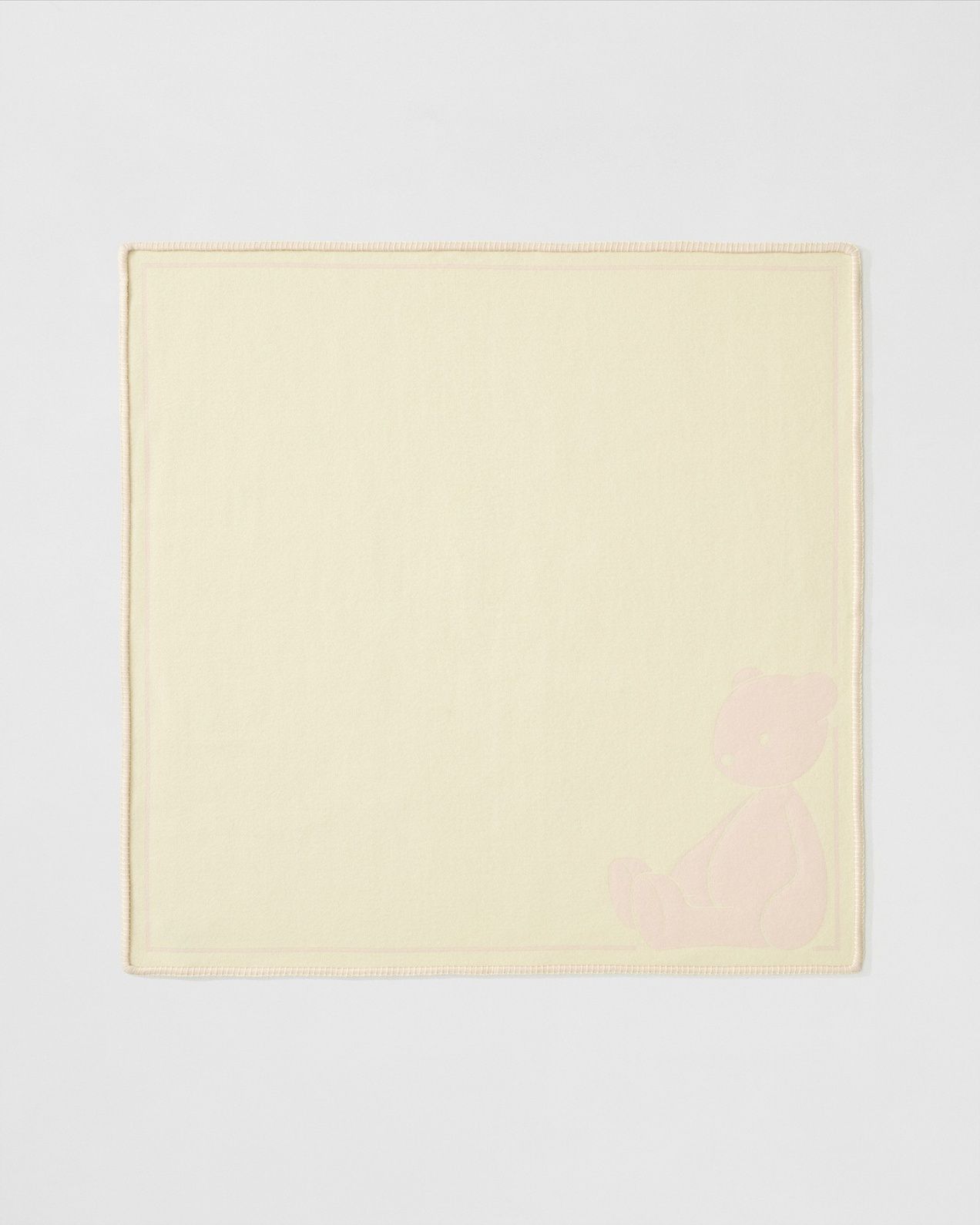

SA: And so, the current collection you’re doing with Kvadrat for children is more of the former?

RS: I think there’s a bit of a misconception there. The kids’ stuff isn’t something we initiated as a thing in itself. It’s actually a continuation of what we initiated when we decided a long time ago to do products for the home. These are products that have a certain function but are decidedly not furniture. They’re things people can use at home—something to hang your keys on, a hat, a towel, a blanket, or a cushion. When we started this, we were just thinking about people’s lives and their homes, asking ourselves how it could be in living rooms, bathrooms, bedrooms, or even the garage. During our brainstorming, we asked ourselves how it would be if there were more kids in the house or if there were dogs and cats.

SA: Why the emphasis on kids?

RS: Because I don’t think you can think about the domestic situation or the lives of people without thinking about kids. Unless you think that the design world doesn’t fit with kids. But that’s not what I think.

I’m always surprised that I never see any advertising from one of the giants that features a sofa with like six kids on it. I would assume that lots of people have their kids on the sofa. But in the advertisements, it’s usually a sofa in grey or beige minimal environment or by the sea—which I always question because who puts a sofa by the sea? Then there’s a beautiful woman or a beautiful woman and a beautiful man. I don’t want to criticize it, I just think it’s very strange. I mean, I remember when Verner Panton would shoot a campaign with furniture in the 1970s and there’d be a bunch of kids. Why don’t we see that now?

This is part of a discussion I’ve been having intensely with some people. And one of the questions that comes up a lot is color. I always ask: why doesn’t anybody use colors? Why are all of our screens grey? Why are all phones grey? Why is every car grey or black? I know it sounds like I’m criticizing, but I’m not. I just don’t understand why all our phones are grey.

If you look at the 1950s, cars had magnificent, beautiful colors. I mean, nature isn’t changing—a flower remains a flower. It still has a beautiful color. And there are millions of beautiful colors. So why is it that anything that is now created by a human…You would assume that humans are becoming smarter and smarter and more and more creative and evolved, but it’s actually the opposite. What’s happening is that people are becoming more politically incorrect and irresponsible towards each other and nature and the climate. I also think they’re becoming somewhat irresponsible in what they design.

SA: I also read that most pop songs that become hits today don’t have chord changes anymore. There used to be wild changes but now everything feels more monotone and monochrome.

RS: Monochrome is a good way of defining it. The one reason I could understand for people going more into neutral tones and flattening everything is when there’s a huge economic responsibility. People go for what’s safe. I get that. But I think that for us as creative initiators, it would be sad if we only offered grey and beige as possibilities. There must be people who want something different or even to have the possibility at least.

I just recently leased a new car. It’s the same car I always use, I won’t name the make. I asked them what the color options were and they looked at me as if I was a complete idiot. They were like, “but don’t you want grey or black?” I said, “maybe I want light blue.” It was like the world was exploding for them. It was very weird and surreal. I was standing in this garage with these car people and thought how strange it is to not even have the possibility to do something different. Then they said they could do it but it would be a two-year wait but the car I had wouldn’t make it that long. So, grey or black it was.

SA: How do you decide on what colors to use?

RS: That’s a very difficult question. I don’t really know. It’s a natural thing. It’s like if I were to ask you: how did you become a journalist? I can’t express myself very well in words or in writing but I express myself with clothes or with design or with colors. I like colors. Purple, mint green… I also like black and beige and grey. And I also know very well that we offer neutral tones and the classicist kinds of colors. I think that’s absolutely ok. I think fashion tends to be beige and camel and two grey tones and marine and black. But I also think you have to offer interesting color options and prints, which many labels do.

What I try to do when I move through the world is observe color all the time, whether that’s walking in nature or swimming underwater. I live in a historical house with stained glass windows depicting a food bouquet. I know all the colors in that bouquet. I think if you asked anyone who visited this house even a hundred times, they wouldn’t be able to say all the colors. But it’s something I’ve always done.

A more difficult question is why I bring certain colors together. I don’t actually know. Maybe it’s because I think they’re interesting or because it’s challenging for myself and therefore a way for people to rethink their relationship to color.

“When Miuccia and I started working together five and a half years ago, our first conversation was about how we’d been doing very extreme, eccentric, and narrative-driven things for decades, but now our biggest challenge was to really deal with reality and people.”

RS: With the Kvadrat collaboration, we start with many colors, which we call color blankets… But actually, we started more than ten years ago with a philosophy around the idea of color, which relates to what we discussing about everything becoming grey. In the early conversations, one of the main things I wanted to communicate to Anders [Byriel, CEO of Kvadrat] was that I wanted to focus on the idea of colors and color juxtaposition and, again, give more possibilities to people. Imagine, you’re in the garage and you see just one pastel in a beautiful color and one beautiful electric blue amongst 30 gray and black cars. Wouldn’t it be sublime? Even if you don’t want it, isn’t it just great that it exists? And you know, it does happen that people choose strong colors. My best friends surprised me. I go to their house like 5, 6, or 7 times a year. They live in a classic historical house, and five years ago, they suddenly had a big bench in a shocking pink. I remember thinking, wow, you’ve got guts. And they were so happy with it and how everyone reacted to it.

SA: You’ve said before that a guiding question in your work is “Would I myself?”—would I wear it, would I live with it? Does that apply when making clothes or designing for children, given that you’re no longer the end user?

RS: I asked myself this question more in the sense of saying, “Is this a joke?” I never asked myself the question in the sense that I only design for myself what I absolutely need to have around me. That’s something I learned over time in fashion. I think when I started out in fashion, I was very much designing for myself. And then you start to understand that you’re having a dialogue with the world without talking. There are so many people in the world who have different interests and needs than you do and so you start addressing them.

I think the question “would I?” is more about not making something that I think is completely ridiculous or unnecessary or not useful. There were times when I asked this more in fashion but at Prada, when Miuccia and I started working together five and a half years ago, our first conversation was about how we’d been doing very extreme, eccentric, and narrative-driven things for decades, but now our biggest challenge was to really deal with reality and people. This dialogue paid off, and not only economically. It also paid off for ourselves. The biggest reward is when you see people wear what you designed. When you see them use it and live with it.

But if we’re talking about the kid’s things for Kvadrat, then I don’t need the teddy bear in the house because I don’t have kids. I mean, I’m sure Goya [Raf Simons’ dog] would be very happy with the teddy bear or even with the blankets.

SA: Why did you include these specific items?

RS: It’s important to say that we’re a group of people—I never really think that I’m doing anything on my own. And so, when we were having these discussions, I wanted to have a stuffed animal. It ended up being this one bear, but if it were up to me, we would have had like 10 different animals. I would have made a dog, a cat, a bear, a rabbit, a snake, and a bat. I’m very obsessed with animals and I used to be obsessed with stuffed animals as a kid. I would collect them, put them on my bed, and organize them. Making it, then, was a kind of emotional memory. I also loved playing with blankets and thought it’d be really nice to have certain things that feel like they could be for many different ages. The cap feels like it’s not for young kids but the blankets could be for babies even.

I’m also interested in the way items are passed down and inherited. I go back to my parents’ house almost every weekend and there are certain objects they kept for me from a very young age that I cherish even if I don’t remember them because your memory can’t go back to when you were like one or two years old. My mom kept this little metal cup and spoon engraved with a squirrel. It was probably in metal because I was so small that I’d throw it on the ground all the time but I don’t remember. If I had a kid, it’s probably one of the first things I’d want to give them.

SA: Were you actively thinking about your own childhood during this project?

RS: Only partly. There was something related to memory as well as something related to authenticity and longevity. Like, if I think about the bear, it’s an emotional thing because I’m an animal lover. I trust animals way more than most people. So, an animal had to be in. But I also remember how I wanted things on my own when I was a child but also things because the adults had it. So, for example, the hooded bath towel is made in the same way that we had in the launch before for adults.

And if you think about children in a house, it can go two ways. The house can either be organized and neat or totally chaotic and a mess. As a child, I was allowed to create a mess. I could turn the whole house upside down and build my own environments with blankets over chairs. But at the end of the afternoon, they also said, “now, clean it up.” So, a blanket can be functional—to give warmth or be cozy—but you can also play with it and do silly things.

SA: The accessories and textiles feel modular—the Shaker system, the storage bags, the blankets. Are you thinking about a kind of open-ended, almost architectural system that grows with a child?

RS: There were two reasons to do the modular system. The first is that I’ve had a strong interest or maybe even an obsession with the Shaker system my whole life. I always thought it was a really sublime system to not hide the things you have around you. They would hang a broom or a chair and when they needed to use them, they’d take them down. Another reason for that is that we have developed a bunch of objects over the years and it’s a tool to install them in a store and create an identity. All the other things are up to the people. We don’t impose anything, ever. That’s how I am as a designer. I think I’m very specific when it comes to how I want to define something or what it should be, but once it goes out, it’s up to the people.

It’s the same with clothes. Sometimes I can be extremely inspired by how people interpret it. Miuccia is the same. We love looking at people. I think I’m only a designer because I love looking at people and the way they dress. I like to observe how they live and what they surround themselves with.

SA: Speaking of which, I understand that you have a large art collection.

RS: It’s my life. More than anything else, I could not have a day without art. It’s not possible. And I don’t mean what surrounds me only. I mean, I need to look at it. I need to read about it. I need to experience it. Many of my friends are artists. If I think about my social world, it’s more in the art world than in the fashion world. This is something I have in common with Anders. He is very dedicated to artists and architects. And he has a very interesting understanding of creative animals. He’s a rare specimen in that he’s patient with creative people. That’s becoming increasingly rare in the creative world that has become such a business. Creatives in art and fashion seem to have less time to perform. Less time to think. And more pressure to economically succeed. But, that’s just where the times are going and we have to follow. As a creator, you shouldn’t complain all the time about that. You go, you do what you believe in, or you get out. I still believe in it. I also think everything goes in waves and that another wave will come at some point. Now, it’s a terribly complicated wave—just like the world is in a terribly complicated phase economically, politically... It’s a disaster.

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson