Factory Diaries: A German Fairytale

|Shane Anderson

When 032c and Birkenstock collaborated on the A630 clog in 2018, Creative Director Maria Koch mentioned that she’s “worn them since forever.” For her, this was nothing out of the ordinary. Birkenstocks are part of everyday life in Germany. And yet, the brand has transcended from being identified with Alltagskultur, which is one of the reasons why I was excited to be invited to visit them.

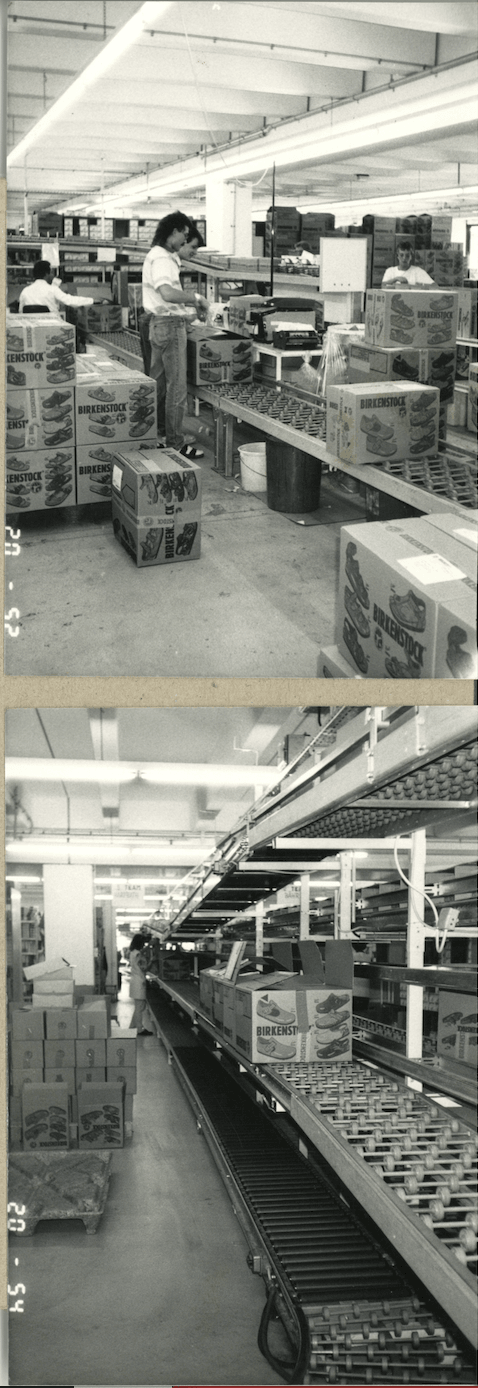

Birkenstock Archive Imagery 1980s

Inside Birkenstock’s factory in Görlitz, I learn that the foot has 28 bones, 33 muscles, and 107 tendons. To serve the natural movement of this intricate machine, the ammoniascented factory hums from early Monday mornings to late Friday nights. We’re told so many numbers on the private tour of the grounds that they become dizzying—but then, so too is the level of demand from across the globe the German brand has reached for its sandals, clogs, and shoes, all produced in the EU. Opened in 2009, this factory produces the original cork latex footbeds and it has ramped up its workforce of footbed bakers, jute punchers, mold changers, process engineers, and other laborers from 190 to about 1,900 today. How did a company dedicated to naturgewolltes Gehen—or, walking as nature intended—ever become such a global sensation?

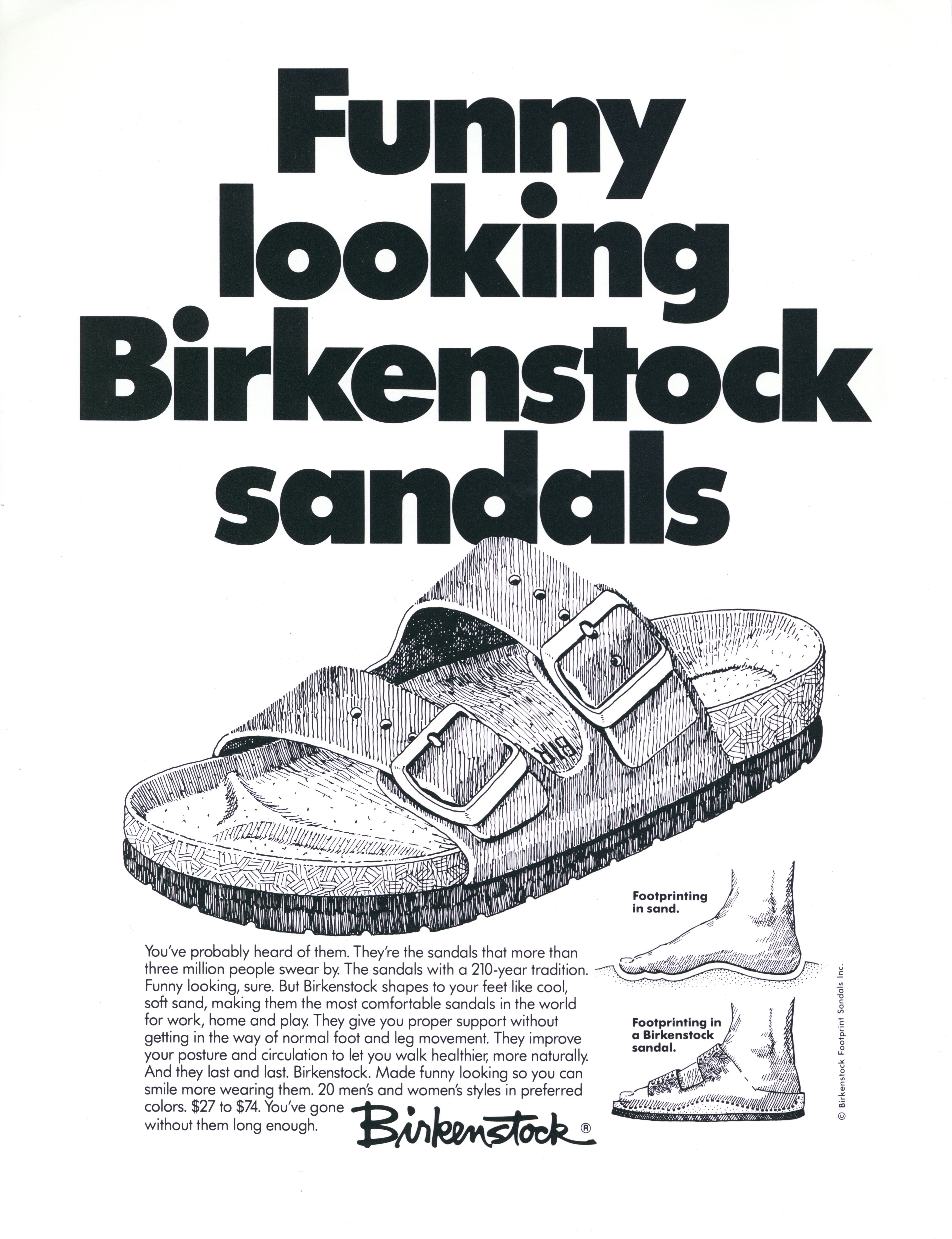

The story began with Johannes Birkenstock, the founder from a dynasty of shoemakers dating back to 1774. Johannes was part of the nineteenth-century revolutionary movements that sought better living and working conditions for craftsmen. By 1896, his son Konrad had moved to Frankfurt—then a hub for innovative shoemaking—and became part of the Natural Reform Movement, which was redefining human health and lifestyle. The orthopedic footbed he developed wasn’t fashion. It was a medical intervention, demonstrated by the patent he registered, called a “healing footbed.” This would be just one of the patents the company would create. Another came from Konrad’s son Carl, who joined the family business in 1915 at the age of fifteen. Driven by the same ideals, Carl sought to create the “ideal shoe.” It followed the principle that “the foot is designed by nature to walk barefoot on soft, uneven ground.” Years of orthopedic study would follow, and in 1951, the patent was successful. Carl was so protective of this technology that he offered foot health courses and only certified graduates could sell his products.

In Görlitz, Bernstadt, Markersdorf, Pasewalk, Uerzell, St. Katharinen, and Arouca— Birkenstock’s seven production sites in Germany and Portugal—this philosophy still takes material form. Today, anyone can buy into the idea of walking naturally with Birkenstock’s iconic built-in cork-latex footbeds—another groundbreaking innovation, which was first introduced in 1963 by Carl’s son, Karl. For the classic footbed, a granulated cork-latex mix is measured into molds, gently baked at a medium temperature, and later joined to leather and buckles with precision. Watching the workers carefully cutting jute and suede, the process reminded me that the past’s craftsmanship is still present in an age of industrial production.

What began as a single contoured footbed has grown into a universe of silhouettes: Arizona, Madrid, Boston, Mayari, Zürich, and Utti. And while we stroll through the factory, we’re told that there are more than 700 styles—spanning price points, seasons, and occasions—yet each pair carries the same DNA of craftsmanship and anatomical precision. And despite sticking to the principles of their family business, Birkenstocks aren’t just shoes. They’re a quiet architecture of the everyday, an attitude. Somewhere between heritage and rebellion, they’ve become symbols of what happens when comfort, function, and design meet on common ground—literally.

Though I am not German, Birkenstocks have become part of my everyday life too. My personal favorites are the Shinjukus, the Velcro-strapped backed sandals with techybuckles that are inspired by Japanese style and that are as at home in the city as on the trail. In fact, you can wear Birkenstocks anywhere. And I do. I have a pair for Hausschuhe, a pair for the beach, and my trusty Shinjukus. What appeals to me about the company is that the sandal that became a fashion object was never designed to be one, which might just be the most radical thing about them.

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson