A Writer Wanted to Run a Marathon, So We Sent Him to Nike Research Labs in Oregon

|Gabriel Proedl

BEAVERTON – Nike City – is a place that feels like it invented itself. Nothing here is arbitrary. The buildings are named after athletes, the asphalt is fresh, and the lawns are cut with mathematical precision. On the paths between the glass facades, employees in black hoodies ride e-bikes and drink light-green juice. Everything seems geared toward sustaining movement as a state of being. Outside, behind the halls, fog rolls in from Oregon’s Columbia River.

I rush toward one of the buildings on the campus to hear CEO Elliott Hill give a speech. He’s charismatic, no doubt, and he dishes out a spiel about how Nike wants to start a movement. Afterward, he comes over to me and asks me what’s up.

“I’m planning on running a half marathon in five days,” I say.

“Good luck, buddy,” he says. Then he’s gone again.

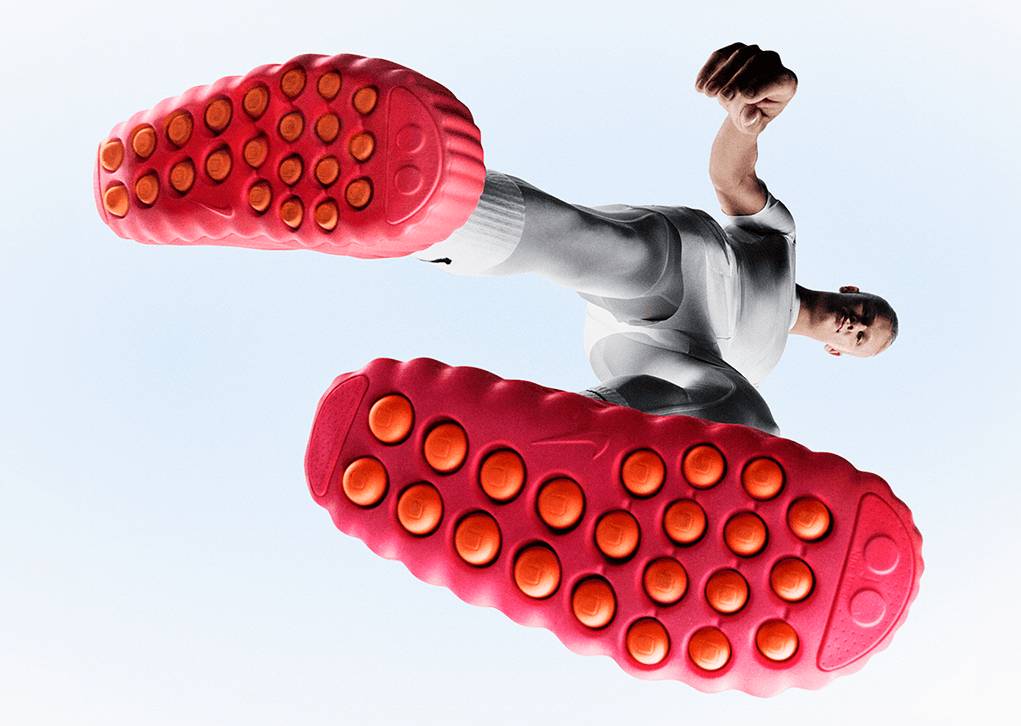

Nike signature athlete Erling Haaland is among hundreds of athletes who tested Nike Mind footwear over the past five years.

Not too long ago, Nike was in a state of economic paralysis. The brand that had, for decades, defined itself through change and speed had lost its rhythm. Too many products, too much lifestyle, too little sports. The previous CEO was put on leave, and Elliott Hill was brought out of retirement – the very man who had started as an intern at Nike in 1988 and, over three decades, got to know the company from the inside out. Hill is known as the “CEO of Sport,” someone who sees the body as the center of everything. Under his leadership, Nike is tightening its reins once again: away from fashion and back toward function, performance, and athletes. It’s a return to what made Nike great in the first place.

Here, at the LeBron James Innovation Center, this notion of movement is taken apart and reassembled. On the top floor of the building, the Nike Sport Research Lab is the technical heart of the company. Split over several floors, the lab analyzes movement and tests materials. “Think big. Fail fast,” I think – one of Nike’s slogans. Or was it “Think fast, fail big”?

I head toward the Fieldhouse Track – an indoor racecourse, 200 meters of rubber, with asphalt and concrete lanes that have cameras, sensors, and force plates. Here, movement isn’t observed; it’s measured. Every step produces data, every footprint a curve. The motion-capture cameras record every joint and every stride on pressure-sensitive treadmills. Researchers from the fields of biomechanics, sports medicine, physiology, and data analysis study how fabrics react to heat, how muscles fatigue, and how sweat evaporates.

You get the sense that no distinction exists between biology and mechanics in Beaverton anymore. The body is treated as a data storage device, movement as information. And there’s a point at which it’s hard to see where the human ends and the measurement begins.

Nike headquarters in Beaverton, Oregon

I have an appointment with TONY BIGNELL, chief innovation officer. We meet in a room next to the track. He used to be a middle-distance runner, but now he develops shoes for world records. “That’s why I understand the athletes’ frustration,” he says. “I can relate.” I tell him that I’m from Vienna, the place where Eliud Kipchoge ran a marathon back and forth through the Prater, on a perfectly straight path lined with chestnut trees. With a time of 1:59:40, Kipchoge became the first human being to finish a marathon under the two-hour mark, and Bignell was the one who designed a special shoe just for him. “That project changed everything,” Bignell says. “It showed that limits only exist until you test them.” I ask how he manages to not lose sight of the real customers, like me, a total amateur, when he’s surrounded by all these special athletes. “You and Kipchoge face the same hurdles,” he says. “You both want to avoid injury. You both want to beat your own records. And you both want to have a good time.”

His advice for my run on Sunday: “The pressure you put on yourself is the same – no matter whether you’re a pro or an amateur.” Fair enough. We shake hands goodbye, and as I’m leaving, he calls after me: “In the end, the mind matters more than the body. Once you learn to keep it calm, the rest follows naturally.” He points at some prototypes, a pair of light gray shoes with fine sensors embedded in the soles.

“It’s a shoe that responds to the brain,” he says. This sounds like science fiction, but it’s a project Nike is running under the rubric neuroscience-based footwear. The new platform is called Mind, and its goal has less to do with speed than with a state of being. It’s about concentration, calm, and what the body does when it’s in balance. It’s ideal before a competition, for example, or on recovery days between training sessions. Erling Haaland, the star striker at Manchester City, will be the face of the campaign. I’m reminded of an iconic quote from one of his interviews: “It’s good to have a little bit of pain here and there.”

The foundation stems from cognitive research conducted at the Nike Sport Research Lab. For years, its researchers have been studying what happens in the brains of athletes when they focus. That study itself focuses not on muscle tension but on neural activity: micro-impulses and frequencies oscillating between tension and release. These patterns were translated into textile and structural responses.

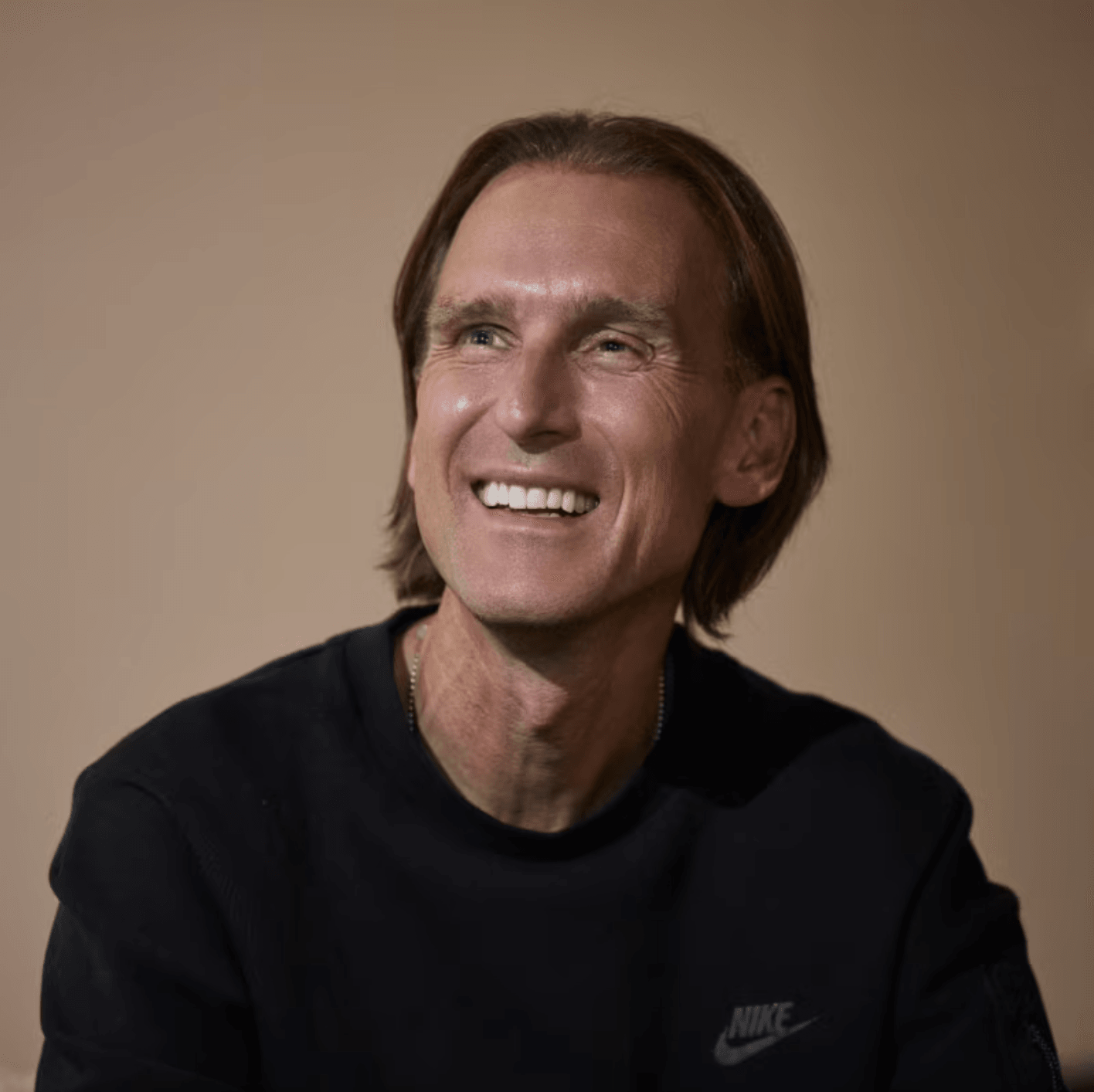

Tony Bignell, Chief Innovation Officer at Nike

The shoe itself looks somewhat unspectacular on the outside. It has no exoskeleton, no electronic features. The crucial element becomes apparent only when you lift the sole: there, a layer of sensor-conductive foam measures minimal changes in pressure on the foot and relays them to an adaptive cushioning system. Within milliseconds, this system regulates how softly or firmly the shoe reacts, depending on whether the body is in flow or in a state of resistance.

A neuroscientist saunters up to me. “Wear it! Feel it!” It sounds like a command. I slip on the shoes and walk a few steps across the artificial turf. And sure enough, I can feel the synthetic blades of grass beneath the soles of my feet, a tickling sensation that’s light and pleasant. “Are you relaxed now?” the scientist asks.

“Well,” I say, “that doesn’t happen just like that, does it?” “It does for me!” he says.

The ensuing relaxation stems from what he calls “neural grounding.” The insole is made of a new composite material that’s tuned to the “gamma-band frequency,” which is associated with presence and focus in the brain. The scientist describes it as a “feedback loop between body and mind.” The product is designed to help induce the state runners sometimes call flow – the brief suspension of effort and will.

In trial runs, athletes report that the shoe feels “calmer.” Not softer or lighter – just more even. The feedback is less of a physical sensation than a shift in mood: less distraction, fewer ups and downs. For Nike, this attempt is but the first to modulate mental states through design – not via an app or algorithm, but instead through the physical object itself.

Addressing the neuroscientist, I suggest that the oldest algorithm in the world is the body, a system that’s been collecting data for millennia – gravity, muscle tension, pain – and constantly recalculating them. The research in Beaverton is trying to decipher this code. Perhaps it’s a mistake to try to optimize it, though. Movement works not because it's perfect, but because it remains incomplete. It's in this gap that everything alive begins.

Akin to how electric bikes have made it easier to ride farther and more frequently, revolutionizing urban commuting, Nike is developing Project Amplify to make slower running, jogging, and walking easier and more fun, with a focus on athletes running between a 10- and 12-minute-mile pace.

The Therma-FIT Air Milano Jacket combines Nike’s iconic Air technology with innovative materials and computational design to provide dynamic warmth and personalized thermal control for athletes in all conditions.

I have an appointment with PHIL MCCARTNEY, the chief innovation, design, and product officer, and we meet in one of the conference rooms. His tone of voice is calm, almost casual, while he shows me an old pair of Nike spikes – his very own, from back when he was a competitive athlete. “When you talk to people here,” he says, “there’s almost always an emotional story behind why they ended up at Nike. For me, it’s these shoes, which I got as a present from a charitable organization as a teenager.”

I ask him if conflict often arises between the teams, innovation versus style.

“Always,” he says. “But, hey, there’s no style without performance and no performance without style. Always remember that.”

McCartney invites me to have a look at some new products. Shirts are on display in a specially designed presentation room. “Can I touch them?”

“Sure, go ahead.”

The fabric is light and has a nice, velvety feel. Very little friction, barely any weight. The idea is that air moves between the skin and the fabric, like a second layer. It’s a system of fabrics that translates the body’s reactions.

“Every drop of sweat that hits the ground doesn’t cool your body,” he says. “It’s lost.”

The new shirts are based on a simple idea: the body is a climate. It’s not a passive surface that just reacts; it’s a system that is regulated in real time. The microclimate of the body is meant to be managed through absorbing sweat, accelerating air circulation, and storing or releasing heat, depending upon the environment. The shirts are made of recycled polyester – 100 percent textile waste that’s been broken down to the molecular level and reassembled into new polyester chips. The resulting yarn has the same quality as newly woven fabric – soft, stretchy, and moisture-regulating.

The real innovation lies in the yarn’s structure. The material is produced on Jacquard machines, which create different knit zones with as many as 6,000 needles per pass. These elliptical mesh zones direct air between the skin and the fabric. As a result, there’s twice as much air permeability, a value engineers measure in cubic feet per minute. The higher the number, the better the air exchange and the faster that sweat evaporates.

One of the centerpieces of the LeBron James Innovation Center is the climate chamber, the place where this logic is tested. Temperatures range from -4°C to more than 50°C, with controlled humidity, wind, and solar radiation. The athletes here wear sensors that track their skin and core temperatures, heart rate, and rate of sweating. Afterward, each garment is weighed to determine exactly how much sweat remained in the fabric and how much evaporated. The goal is to find the perfect balance: enough evaporation to cool the body, but not so much that energy is lost.

Phil McCartney, Chief Innovation, Design and Product Officer, Nike, Inc.

The co-creator of this technology, JANETT NICHOL, vice president of apparel innovation, is waiting for me in a glass-walled room next to the climate chamber. Outside, testers wired with sensors are playing soccer, and streams of data flicker across the screens. Nichol has been at Nike for more than 30 years – she’s seen every idea that has come and gone.

“I believe in what people are capable of,” she says. “I came to Nike as a designer, but at some point, I realized that this is more than just design. It’s about helping people push beyond their own limits.” She doesn’t speak about victory or performance but instead about movement as an attitude. “Whether it’s an athlete or just someone who wants to give their very best – I believe that sport helps to move the world forward.”

I tell her that I’m going to be running a half marathon on Sunday. She looks at me and laughs a little. “Then you’re definitely going to need some reinforcement,” she says. She tells me about a pair of shoes that are still in the testing phase: “Amplify. Basically, anything is possible with these. They’re engines for your legs.”

A motor in your shoes: not a metaphor, as many other things are at Nike, but a real physical system. They call this experiment Project Amplify. Developed in laboratories here, it’s a “powered footwear system” for walking and running. It’s intended not to replace movement but instead to enhance it.

The idea is simple. A lightweight electric motor sits above the heel, which is connected to a drive belt that relieves pressure on the lower leg. A small rechargeable battery is integrated into a cuff at the ankle. The shoe itself is based on a classic running model with a carbon plate, and the mechanism can be attached or detached.

Amplify was developed together with Dephy, a robotics partner base in Massachusetts that usually builds exoskeletons for medical rehabilitation and the military. The aim is to support movement when the foot leaves the ground, which is where the most energy is lost. The motor delivers a small impulse, almost imperceptible but measurable. In tests, many athletes were able to run 10 percent to 15 percent farther with the same amount of energy expended. In some cases, a seven-and-a-half-minute kilometer became a six-minute kilometer, with no extra effort.

The science behind it has to do with biomechanics. Fed by millions of data points, movement algorithms analyze natural stride frequency, roll-off timing, and muscle fatigue. The shoe amplifies what happens naturally and deactivates when there’s a change in the rhythm of movement. The developers call it “assist-as-needed” – help only when the body demands it.

Project Amplify makes it easier for everyday athletes to walk or run more often, for longer amounts of time, while having more fun – adding movement to their lives, extending their walking commute, or helping them to enjoy the run for another mile or two.

Then I get to take a look at the test track: more than 400 participants have tested the system here, taking in excess of 2.4 million steps in total. The sensors on the lab’s 200-meter track record 2,500 data points per second: pressure, angle of impact, and energy expenditure. On the ceiling up above, 250 cameras scan every movement in 3D, and down on the track, force plates measure the contact with the ground. Within this dense landscape of data, the first generation of the system was born.

But how much help is still human? Amplify is intended not for elite athletes, but instead for everyone who runs but doesn’t have to win. “It’s an e-bike for the body,” says Michael Donaghu, one of Amplify’s developers. A second calf muscle, discreet and pragmatic, it doesn’t replace exercise, but it does replace doubt: that moment when your body grows tired and your head decides that it’s had enough. I’m allowed to test the device.

In the building’s entrance, a steep concrete ramp of stairs leads upward, a motion sensor embedded in each step. I lace up Amplify and feel a faint hum, barely noticeable. The first steps feel strange, as if the shoe is deciding how far I should go before I do. The mechanism kicks in. One step, then another. It feels wrong, almost alien. But I keep walking, several hundred meters, up and down the steep ramp. I’m eventually exhausted, so I unfasten the cuff from the shoe and the motor stops. Everything is suddenly heavier, more normal. It’s as if I got off a trampoline after jumping around for a long time. I understand what Nichol meant. The shoe isn’t a substitute for working out, it just carries you past the moment when the mind would otherwise call it quits.

The Nike Sport Research Lab has incorporated mind sciences (studies of sensory and cognitive tasks in the brain) as a growing area of expertise alongside biomechanics, exercise physiology, and functional anatomy.

In the same building, Nichol shows me something else. Not a shoe this time, but a piece of fabric. She insists that I’ll “absolutely need it for [my] run.” After all the motors and measurements, it seems almost banal at first. But this product, too, is about energy, just in a different form.

The jacket is called Air Milano and is part of the next generation of Air technology. It transfers the principle of cushioning – that of enclosed, controlled air – into a textile form. Air as material, not as empty space.

At its core, the garment is a thermoregulating system: a combination of aero-yarns, knit chambers, and membrane zones that store or release heat as needed. It was developed here in Oregon, in the same halls where Air soles have been manufactured for decades. In this case, the makers are not sealing air pockets into soles but weaving them into fabrics.

The jacket remains light, compressible, and almost silent. When you move, it generates subtle differences in pressure that allow air to circulate through the chambers. This flow allows it to function like an adaptive shell, adjusting to temperature and activity.

Its public debut is already scheduled, and Air Milano will be worn for the first time at the upcoming Winter Olympics in February as part of the official USA team uniform. This fits in with the current mood in the country. In a return to its own iconography, the United States is experiencing a new surge in enthusiasm about athletics: Los Angeles is preparing for the 2028 Summer Games; Mexico City and the USA are co-hosting the World Cup; and in Beaverton, Oregon, Nike is designing the accompanying aesthetic program. Sports are seen here as an infrastructure for self-confidence. Nike wants to be back on top.

As I leave the building, the wind smells of rain, and I’m cold and exhausted. In the end, the body remains the only system we’ll never fully understand. It reacts, compensates, fails, and reinvents itself. While I crouch by the side of the road and wait for a taxi, I watch one of the most iconic Nike commercials via my iPhone. Filmmaker Spike Lee, as his Mars Blackmon character, is standing on an indoor basketball court with Michael Jordan, and the two of them are looking straight into the camera.

Lee: “Yo, Mike, what makes you the best player in the universe? Is it the vicious dunks?”

Jordan: “No!”

Lee: “Is it the haircut?”

Jordan: “No!”

Lee: “The shoes, then, right?” (He holds up a Nike shoe for the camera.)

Jordan: “Nah!”

Lee: “It’s got to be the shoes!”

Jordan: “No!”

After this short exchange, a note from Nike appears on screen: “Mr. Jordan’s opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Nike, Inc.”

I smile. But it’s true: Nike puts the runners as well as the basketball and soccer players at the center, and here on the campus, they develop products around the clock so that athletes can jump higher and run faster. But the athletes still have to do the running and jumping themselves. It all comes down to them. To their fitness, their mental strength, and their will to succeed.

My taxi arrives. There are just a few days until the race.

Credits

- Text: Gabriel Proedl